If you are unable to finish the lab in the ProLUG lab environment we ask you

rebootthe machine from the command line so that other students will have the intended environment.

Resources / Important Links

Required Materials

- Rocky 9.4+ - ProLUG Lab

- Or comparable Linux box

- root or sudo command access

Downloads

The lab has been provided for convenience below:

Pre-Lab Warm-Up

EXERCISES (Warmup to quickly run through your system and familiarize yourself)

mkdir lab_essentials

cd lab_essentials

ls

touch testfile1

ls

touch testfile{2..10}

ls

# What does this do differently?

# Can you figure out what the size of those files are in bytes? What command did you use?

touch file.`hostname`

touch file.`hostname`.`date +%F`

touch file.`hostname`.`date +%F`.`date +%s`

ls

# What do each of these values mean? `man date` to figure those values out.

# Try to set the following values in the file

# year, just two digits

# today's day of the month

# Just the century

date +%y

date +%e

date +%C

Lab 🧪

This lab is designed to help you get familiar with the basics of the systems you will be working on. Some of you will find that you know the basic material but the techniques here allow you to put it together in a more complex fashion.

It is recommended that you type these commands and do not copy and paste them. Word sometimes likes to format characters and they don’t always play nice with Linux.

Working with files:

# Creating empty files with touch

touch fruits.txt

ls -l fruits.txt

# You will see that fruits.txt exists and is a 0 length (bytes) file

-rw-r--r--. 1 root root 0 Jun 22 07:59 fruits.txt

# Take a look at those values and see if you can figure out what they mean.

# man touch and see if it has any other useful features you might use. If

# you’ve ever used tiered storage think about access times and how to keep data

# hot/warm/cold. If you haven’t just look around for a bit.

rm -rf fruits.txt

ls -l fruits.txt

# You will see that fruits.txt is gone.

Creating files just by stuffing data in them:

echo “grapes 5” > fruits.txt

cat fruits.txt

echo “apples 3” > fruits.txt

cat fruits.txt

echo “ “ > fruits.txt

echo “grapes 5” >> fruits.txt

cat fruits.txt

echo “apples 3” >> fruits.txt

cat fruits.txt

What is the difference between these two? Appending a file >> adds to the file whereas > just overwrites the file each write. Log files almost always are written with >>, we never > over those types of files.

Creating file with vi or vim:

# It is highly recommended the user read vimtutor. To get vimtutor follow

# these steps:

sudo -i

yum -y install vim

vimtutor

# There are about 36 short labs to show a user how to get around inside of vi.

# There are also cheat sheets around to help.

vi somefile.txt

# type “i” to enter insert mode

# Enter the following lines

grapes 5

apples 7

oranges 3

bananas 2

pears 6

pineapples 9

# hit the “esc” key at the top left of your keyboard

# Type “:wq”

# Hit enter

cat somefile.txt

Copying and moving files:

cp somefile.txt backupfile.txt

ls

cat backupfile.txt

mv somefile.txt fruits.txt

ls

cat fruits.txt

Look at what happened in each of these scenarios. Can you explain the difference between cp and mv? Read the manuals for cp and mv to see if there’s anything that may be useful to you. For most of us -r is tremendously useful option for moving directories.

Searching/filtering through files:

# So maybe we only want to see certain values from a file, we can filter

# with a tool called grep

cat fruits.txt

cat fruits.txt | grep apple

cat fruits.txt | grep APPLE

# read the manual for grep and see if you can cause it to ignore case.

# See if you can figure out how to both ignore case and only find the

# word apple at the beginning of the line.

# If you can’t, here’s the answer. Try it:

cat fruits.txt | grep -i "^apple"

Can you figure out why that worked? What do you think the ^ does? Anchoring is a common term for this. See if you can find what anchors to the end of a string.

Sorting files with sort:

# Let’s sort our file fruits.txt and look at what happens to the output

# and the original file

sort fruits.txt

cat fruits.txt

# Did the sort output come out different than the cat output? Did sorting

# your file do anything to your original data? So let’s sort our data again

# and figure out what this command does differently

sort -k 2 fruits.txt

# You can of course man sort to figure it out, but -k refers to the “key” and

# can be useful for sorting by a specific column

# But, if we cat fruits.txt we see we didn’t save anything we did. What if we

# wanted to save these outputs into a file. Could you do it? If you couldn’t,

# here’s an answer:

sort fruits.txt > sort_by_alphabetical.txt

sort -k 2 fruits.txt > sort_by_price.txt

# Cat both of those files out and verify their output

Advanced sort practice:

# Consider the command

ps -aux

# But that’s too long to probably see everything, so let’s use a command

# to filter just the top few lines

ps -aux | head

# So now you can see the actual fields (keys) across the top that we could sort by

USER PID %CPU %MEM VSZ RSS TTY STAT START TIME COMMAND

# So let’s say we wanted to sort by %MEM

ps -aux | sort -k 4 -n -r | head -10

Read man to see why that works. Why do you suppose that it needs to be reversed to have the highest numbers at the top? What is the difference, if you can see any, between using the -n or not using it? You may have to use head -40 to figure that out, depending on your processes running.

Read man ps to figure out what other things you can see or sort by from the ps command. We will examine that command in detail in another lab.

Working with redirection:

The good thing is that you’ve already been redirecting information into files. The > and >> are useful for moving data into files. We have other functionality within redirects that can prove useful for putting data where we want it, or even not seeing the data.

Catching the input of one command and feeding that into the input of another command We’ve actually been doing this the entire time. “|” is the pipe operator and causes the output of one command to become the input of the second command.

cat fruits.txt | grep apple

# This cats out the file, all of it, but then only shows the things that

# pass through the filter of grep. We could continually add to these and make

# them longer and longer

cat fruits.txt | grep apple | sort | nl | awk ‘{print $2}’ | sort -r

pineapples

apples

cat fruits.txt | grep apple | sort | nl | awk '{print $3}' | sort -r

9

7

cat fruits.txt | grep apple | sort | nl | awk '{print $1}' | sort -r

2

1

# Take these apart by pulling the end pipe and command off to see what is

# actually happening:

cat fruits.txt | grep apple | sort | nl | awk '{print $1}' | sort -r

2

1

cat fruits.txt | grep apple | sort | nl | awk '{print $1}'

1

2

cat fruits.txt | grep apple | sort | nl

1 apples 7

2 pineapples 9

cat fruits.txt | grep apple | sort

apples 7

pineapples 9

cat fruits.txt | grep apple

apples 7

pineapples 9

See if you can figure out what each of those commands do.

Read the manual man command for any command you don’t recognize.

Use something you learned to affect the output.

Throwing the output into a file:

We’ve already used > and >> to throw data into a file but when we redirect like that we are catching it before it comes to the screen. There is another tool that is useful for catching data and also showing it to us, that is tee.

date

# comes to the screen

date > datefile

# redirects and creates a file datefile with the value

date | tee -a datefile

# will come to screen, redirect to the file.

Do a quick man on tee to see what the -a does. Try it without that value. Can you see any other useful options in there for tee?

Ignoring pesky errors or tossing out unwanted output:

Sometimes we don’t care when something errs out. We just want to see that it’s working or not. If you’re wanting to filter out errors (2) in the standarderr, you can do this

ls fruits.txt

# You should see normal output

ls fruity.txt

# You should see an error unless you made this file

ls fruity.txt 2> /dev/null

# You should no longer see the error.

# But, sometimes you do care how well your script runs against 100 servers,

# or you’re testing and want to see those errors. You can redirect that to a file, just as easy

ls fruity.txt 2> error.log

cat error.log

# You’ll see the error. If you want it see it a few times do the error line to see it happen.

In one of our later labs we’re going to look at stressing our systems out. For this, we’ll use a command that basically just causes the system to burn cpu cycles creating random numbers, zipping up the output and then throwing it all away. Here’s a preview of that command so you can play with it.

May have to yum -y install bzip2 for this next one to work.

time dd if=/dev/urandom bs=1024k count=20 | bzip2 -9 >> /dev/null

Use “crtl + c” to break if you use that and it becomes too long or your system is under too much load. The only numbers you can play with there are the 1024k and the count. Other numbers should be only changed if you use man to read about them first.

This is the “poor man’s” answer file. Something we used to do when we needed to answer some values into a script or installer. This is still very accurate and still works, but might be a bit advanced with a lot of advanced topics in here. Try it if you’d like but don’t worry if you don’t get this on the first lab.

vi testscript.sh

hit “i” to enter insert mode

add the following lines:

#!/bin/bash

read value

echo "The first value is $value"

read value

echo "The second value is $value"

read value

echo "The third value is $value"

read value

echo "The fourth value is $value"

# hit “esc” key

type in :wq

# hit enter

chmod 755 testscript.sh

# Now type in this (don’t type in the > those will just be there in your shell):

[xgqa6cha@N01APL4244 ~]$ echo "yes

> no

> 10

> why" | ./testscript.sh

> yes

> no

> 10

> why

What happened here is that we read the input from command line and gave it, in order to the script to read and then output. This is something we do if we know an installer wants certain values throughout it, but we don’t want to sit there and type them in, or we’re doing it across 100 servers quickly, or all kinds of reasons. It’s just a quick and dirty input “hack” that counts as a redirect.

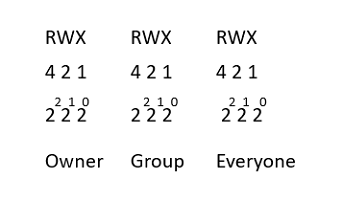

Working with permissions:

Permissions have to do with who can or cannot access (read), edit (write), or execute (xecute)files.

Permissions look like this.

ls -l

| Permission | # of Links | UID Owner | Group Owner | Size (b) | Creation Month | Creation Day | Creation Time | File Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -rw-r--r--. | 1 | Root | root | 58 | Jun | 22 | 08:52 | datefile |

The primary permissions commands we’re going to use are going to be chmod (access) and chown (ownership).

A quick rundown of how permissions break out:

Let’s examine some permissions and see if we can’t figure out what permissions are allowed.

ls -ld /root/

# drwx------. 5 root root 4096 Jun 22 09:11 /root/

The first character lets you know if the file is a directory, file, or link. In this case we are looking at my home directory.

rwx: For UID (me).

- What permissions do I have?

---: For group.

- Who are they?

- What can my group do?

---: For everyone else.

- What can everyone else do?

Go find some other interesting files or directories and see what you see there. Can you identify their characteristics and permissions?

Be sure to

rebootthe lab machine from the command line when you are done.